This feed omits posts by rms. Just 'cause.

Since nobody reads to the end of my posts I’ll start this one with the actionable experiment:

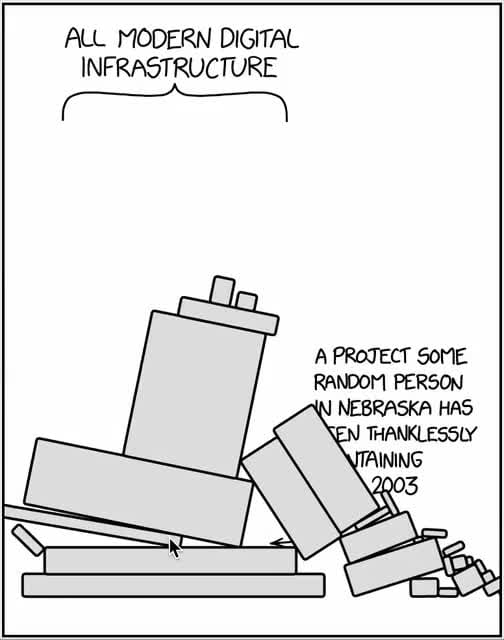

Deep neural network have a fundamental problem. The thing which makes them able to be trained also makes them susceptible to Manchurian Candidate type attacks where you say the right gibberish to them and it hijacks their brain to do whatever you want. They’re so deeply susceptible to this that it’s a miracle they do anything useful at all, but they clearly do and mostly people just pretend this problem is academic when using them in the wild even though the attacks actually work.

There’s a loophole to this which it might be possible to make reliable: thinking. If an LLM spends time talking to itself then it might be possible for it to react to a Manchurian Candidate attack by initially being hijacked but then going ‘Wait, what am I talking about?’ and pulling itself together before giving its final answer. This is a loophole because the final answer changes chaotically with early word selection so it can’t be back propagated over.

This is something which should explicitly be trained for. During training you can even cheat and directly inject adversarial state without finding a specific adversarial prompt which causes that state. You then get its immediate and post-thinking answers to multiple choice questions and use reinforcement learning to improve its accuracy. Make sure to also train on things where it gets the right answer immediately so you aren’t just training to always change its answer. LLMs are sneaky.

Now on to rambling thoughts.

Some people nitpicked that in my last post I was a little too aggressive not including normalization between layers and residuals, which is fair enough, they are important and possibly necessary details which I elided (although I did mention softmax), but they most definitely play strictly within the rules and the framework given, which was the bigger point. It’s still a circuit you can back propagate over. There’s a problem with online discourse in general, where people act like they’ve debunked an entire thesis if any nitpick can be found, even if it isn’t central to the thesis or the nitpick is over a word fumbling or simplification or the adjustment doesn’t change the accuracy of the thesis at all.

It’s beautifully intuitive how the details of standard LLM circuits fit together: Residuals stop gradient decay. Softmax stops gradient explosion. Transformers cause diffusion. Activation functions add in nonlinearity. There’s another big benefit of residuals which I find important but most people don’t worry about: If you just did a matrix multiplication then all permutations of the outputs would be isomorphic and have valid encodings effectively throwing away log(N!) bits from the weights which is a nontrivial loss. Residuals give an order and make the permutations not at all isomorphic. One quirk of the vernacular is that there isn’t a common term for the reciprocal of the gradient, the size of training adjustments, which is the actual problem. When you have gradient decay you have adjustment explosion and the first layer weights become chaotic noise. When you have gradient explosion you have adjustment decay and the first layer weights are frozen and unchanging. Both are bad for different reasons.

There are clear tradeoffs between fundamental limitations and practical trainability. Simple DNNs get mass quantities of feedback but have slightly mysterious limitations which are terrifying. Thinking has slightly less limitations at the cost of doing the thinking both during running and training where it only gets one unit of feedback per entire session instead of per word. Genetic algorithms have no limitations on the kinds of functions then can handle at all at the cost of being utterly incapable of utilizing back propagation. Simple mutational hill climbing has essentially no benefit over genetic algorithms.

On the subject of activation functions, sometimes now people use Relu^2 which seems directly against the rules and only works by ‘divine benevolence’. There must be a lot of devil in the details in that its non-scale-freeness is leveraged and everything is normed to make the values mostly not go above 1 so there isn’t too much gradient growth. I still maintain trying Reluss is an experiment worth doing.

Some things about the structure of LLMs are bugging me (This is a lot fuzzier and more speculative than the above). In the later layers the residuals make sense but for the first few they’re forcing it to hold onto input information in its brain while it’s trying to form more abstract thoughts so it’s going to have to arbitrarily pick some bits to sacrifice. Of course the actual inputs to an LLM have special handling so this may not matter, at least not for the main part of everything. But that raises some other points which feel off. The input handling being special is a bit weird, but maybe reasonable. It still has the property that in practice the input is completely jamming the first layer for a simply practical reason: The ‘context window’ is basically the size of its brain, and you don’t have to literally overwhelm the whole first layer with it, but if you don’t you’re missing out on potentially useful content, so in practice people overwhelm its brain and figure the training will make it make reasonable tradeoffs on which tokens it starts ignoring, although I suspect in practice it somewhat arbitrarily picks token offsets to just ignore so it has some brain space to think. It also feels extremely weird that it has special weights for all token offset. While the very last word is special and the one before that less so, that goes down quickly and it seems wrong that the weights related the hundredth to hundred and first token back are unrelated to the weights related to the hundred and first and hundred and second token back. Those should be tied together so it’s getting trained as one thing. I suspect that some of that is redundant and inefficient and some of it it is again ignoring parts of the input so it has brain space to think.

/blog/2014/12/30/411x480 /blog/2014/12/30/500x417 /blog/2018/05/12/2048x1365 /blog/2018/05/12/736x677 /blog/2018/05/12/3000x2049 /blog/2018/05/12/2400x1600 /blog/2014/12/30/500x638 /blog/2024/1920x1440 /blog/2015/08/3375x2561 /blog/2015/08/600x600 /blog/2017/08/page/2/1400x781 /blog/2017/08/page/2/1280x720 /blog/2017/08/page/2/464x363 /blog/2017/08/page/2/1200x1600 /blog/2010/03/07/480x640 /blog/2011/09/312x360 /blog/2011/09/640x423 /blog/2011/09/600x800 /blog/2006/09/page/4/1042x673 /blog/2018/03/550x826 /blog/2018/03/640x427 /blog/2018/03/754x1024 /blog/2018/03/815x600 /blog/tag/www/page/2/410x630 /blog/tag/www/page/2/1200x809 /blog/tag/www/page/2/600x900 /blog/2016/04/page/3/962x1779 /blog/2016/04/page/3/1100x568 /blog/2016/04/page/3/1100x568 /blog/2016/04/page/3/1200x848 /blog/tag/www/768x1087 /blog/2014/2692x2970 /blog/tag/www/768x1087 /blog/tag/www/480x360 /blog/tag/www/906x222 /blog/tag/www/480x360 /blog/tag/www/768x270 /blog/2018/01/page/2/450x337 /blog/2018/01/page/2/500x667 /blog/2017/11/teeth-4/500x624 /blog/tag/www/988x1354 /blog/tag/www/800x450 /blog/tag/www/2000x2000 /blog/tag/www/2000x2000 /blog/tag/www/625x512 /blog/tag/www/768x432 /blog/tag/www/615x297 /blog/2014/640x360 /blog/2018/01/page/2/300x450 /blog/2014/1741x2600 /blog/tag/www/712x600 /blog/2018/01/page/2/585x350 /blog/2021/11/page/3/753x1200 /blog/2021/11/page/3/753x1200 /blog/2021/11/page/3/900x563 /blog/2021/11/page/3/1280x960 /blog/2022/05/page/2/1103x300 /blog/2022/05/page/2/1103x300 /blog/2018/07/page/4/315x450 /blog/2022/05/page/2/300x364 /blog/2018/07/page/4/2203x2938 /blog/2014/02/09/400x300 /blog/tag/dazzle/page/2/562x562 /blog/tag/dazzle/page/2/668x960 /blog/tag/dazzle/page/2/950x538 /blog/2006/02/blobby-art/500x375 /blog/tag/dazzle/page/2/484x604 /blog/tag/dazzle/page/2/3300x2475 /blog/tag/katrina/1318x1078 /blog/2019/03/page/3/680x510 /blog/tag/fanboys/768x547 /blog/tag/fanboys/768x1064 /blog/tag/fanboys/575x452 /blog/tag/fanboys/512x512 /blog/tag/fanboys/360x480 /blog/tag/fanboys/768x513 /blog/tag/fanboys/1024x759 /blog/tag/fanboys/584x328 /blog/2010/12/page/3/768x512 /blog/2010/12/page/3/500x628 /blog/2010/12/page/3/500x628 /blog/2010/12/page/3/960x1280 /blog/2010/12/page/3/960x1280 /blog/2019/07/02/500x392 /blog/2019/07/02/388x517 /blog/2019/07/02/388x517 /blog/2013/05/12/468x468 /blog/2019/04/01/900x1200 /blog/2019/04/01/1297x846 /blog/2019/04/01/768x432 /blog/2019/04/01/768x428 /blog/2023/12/shrimpfluencer/640x1136 /blog/2019/04/01/1200x628 /blog/2016/11/page/3/768x1024 /blog/2005/07/page/4/520x503 /blog/2005/07/page/4/520x503 /blog/2005/07/page/4/409x309 /blog/2023/12/psychedelic-cryptography/600x594 /blog/2021/01/page/4/1200x800 /blog/2021/01/page/4/1200x633

Of course all of them claim to be Chrome on "Windows NT 10.0".

The details were finally released last week: [...] That's 7.5 million to 30 million litres of drinking water every single day. This is the reservoir's entire remaining capacity. Google is taking absolutely the limit of all the water they can.

How about the other AI vendors, like OpenAI? [...] Notice what Altman did there -- he started with the headline claim "water is totally fake" then he gave a made-up example ending with "or whatever." What he did not give was anything like a number. A current number. [...]

Given the secrecy, assume all the hyperscalers use a huge amount of fresh water. Until they give us official numbers somewhere they're not allowed to lie. They're not fighting to keep the numbers secret because they're good.

Previously, previously, previously, previously, previously, previously.

Monarch, Legacy of Monsters has a fantastic title sequence. Since the show takes place in two timelines, they split the titles between the past on the left and the present on the right, contrasting similar events in each timeline. And season 2 keeps up this conceit, but it was completely rebuilt!

So here are all four quadrants from seasons 1 and 2, stacked.

Also, this show is still killing it.

In my online undergraduate P5.js course, students are about to begin the module on motion and physics, including a bit of physics simulation using Matter.js. It suddenly occurred to me that I had never seen anybody put together this particular demo before, and I realized it had to be done. Messy source code here.

Previously, previously, previously, previously, previously, previously.

E.g. "unicrud --block Katakana".

The actual XFT font I get from XftFontOpenXlfd("-*-sans serif-bold-r-*-*-*-180-*-*-*-*-*-*") is

Noto Sans-300 :familylang=en :style=Bold :stylelang=en :fullname=Noto Sans Bold :fullnamelang=en :slant=0 :weight=200 :width=100 :pixelsize=401.899 :foundry=GOOG :antialias=True :hintstyle=1 :hinting=True :verticallayout=False :autohint=False :globaladvance=True :file=/usr/share/fonts/truetype/noto/NotoSans-Bold.ttf :index=0 :outline=True :scalable=True :dpi=96.4557 :rgba=5 :scale=1 :minspace=False :fontversion=131334 :capability=otlayout\:DFLT otlayout\:cyrl otlayout\:grek otlayout\:latn :fontformat=TrueType :embolden=False :embeddedbitmap=True :decorative=False :lcdfilter=1 :namelang=en :prgname=unicrud :postscriptname=NotoSans-Bold :color=False :symbol=False :variable=False :fonthashint=True :order=0 :namedinstance=False :fontwrapper=SFNT

The articles, produced in collaboration with the investigative collective WAV, detailed a years-long, multi-ministry charm offensive by Palantir to sell its software to Swiss federal authorities. The campaign was, by all accounts, a comprehensive failure. Swiss agencies rejected Palantir at least nine times, with concerns ranging from data sovereignty to reputational risk to the simple fact that nobody needed the product. [...]

So how does a sophisticated data intelligence company respond to well-sourced investigative journalism based on official government documents?

By suing the journalists, of course.

Previously, previously, previously, previously, previously, previously, previously.

In 1995 someone could have written a paper which went like this (using modern vernacular) and advanced the field of AI by decades:

The central problem with building neural networks is training them when they’re deeper than two layers due to gradient descent and gradient decay. You can get around this problem by building a neural network which has N values at each layer which are then multiplied by an NxN matrix of weights and have Relu applied to them afterwards. This causes the derivative of effects on the last layer to be proportionate with the effects on the first layer no matter how deep the neural network is. This represents a quirky family of functions whose theoretical limitations are mysterious but demonstrably work well for simple problems in practice. As computers get faster it will be necessary to use a sub-quadratic structures for the layers.

History being the quirky thing that it is what actually happened is decades later the seminal paper on those sub-quadratic structures happened to stumble across making everything sublinear and as a result people are confused as to which is actually the core insight. But the structure holds: In a deep neural network, you stick to relu, softmax, sigmoid, sin, and other sublinear functions and magically can train neural networks no matter how deep they are.

There are two big advantages which digital brains have over ours: First, they can be copied perfectly for free, and second, as long as they haven’t diverged too much the results of training them can be copied from one to another. Instead of a million individuals with 20 years experience you get a million copies of one individual with 20 million years of experience. The amount of training data current we humans need to become useful is miniscule compared to current AI but they have the advantage of sheer scale.

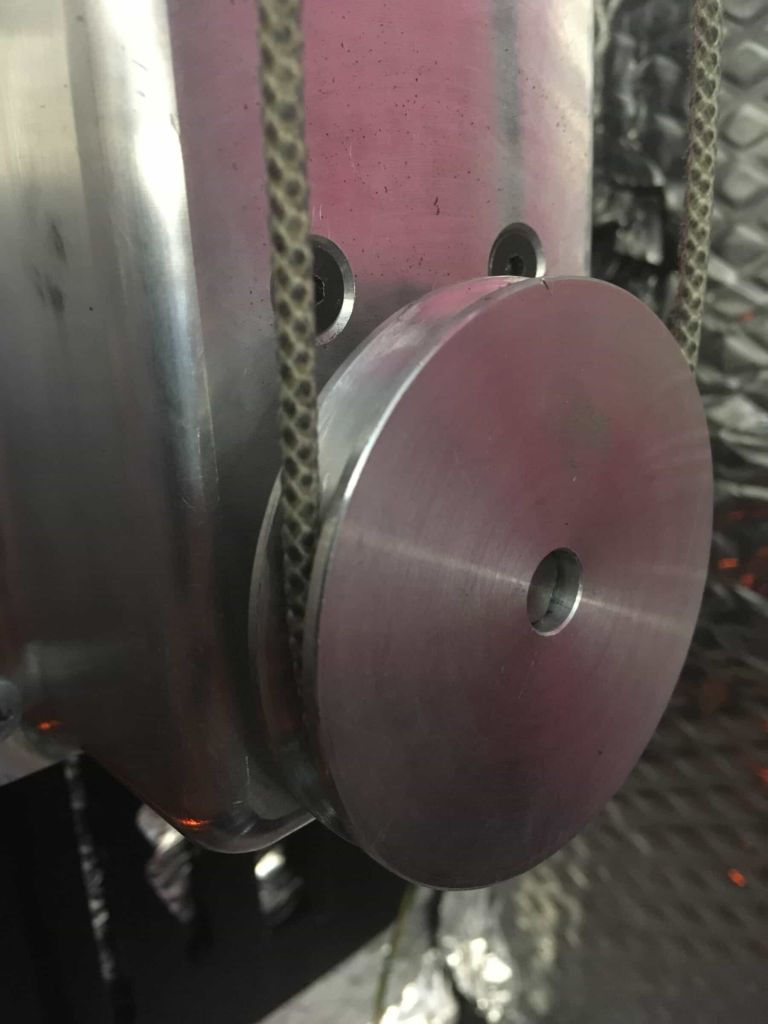

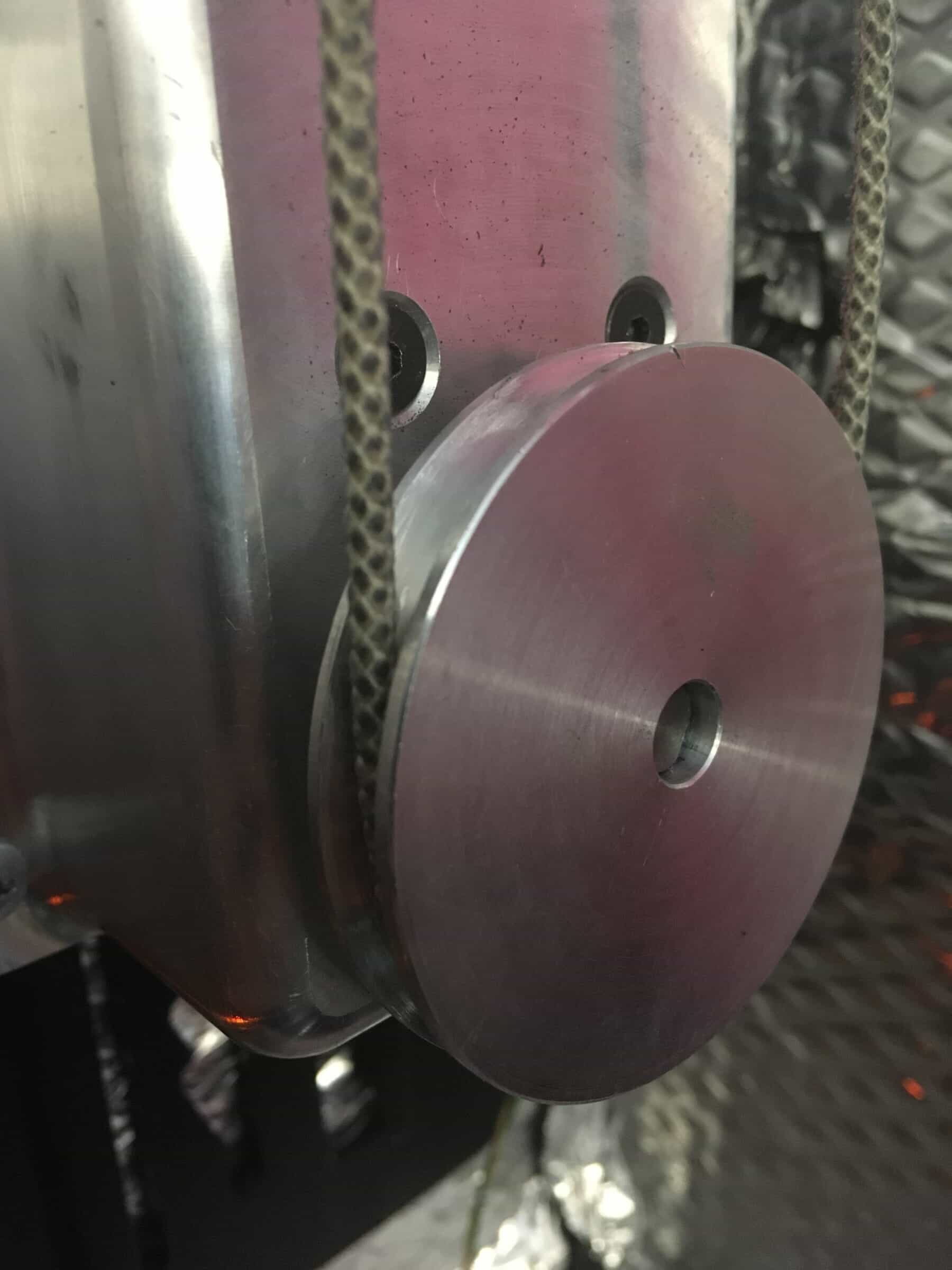

I have this pulley wheel, 50mm inside diameter, 4mm groove. I need a rubber traction ring to go inside it. I cannot find anyone who will sell this to me.

The ring must be flat or concave, not round like a typical gasket seal O-ring, or the string its pulling will just slide off the track.

Alternately, any similar-sized metal pulley wheel that comes with a friction surface pre-attached, 8mm axis hole with set screw.

I have tried coating it with sugru, but that is too soft and wears off after not-very-long.

Update: If you're going to say "why don't you just" or "have you searched for" without a purchase link to a product of the correct size, please know that you are not helping.

Yes, naturally, you would need a prosthetic butthole for this movie about a celibate religious sect, Amanda. I completely agree.

"I was pregnant and naked, but I wasn't naked at all, and at the end of the movie, I'm standing in front of a burning building with just a merkin," she explained. "I felt so free."

Unfortunately, she did clarify: "You cannot see my butthole in the scene, but I swear there is a prosthetic butthole there." Release the butthole cut.

Jason Scott of Internet Archive was kind enough to digitize them for us. And these nearly-40-year-old VHS tapes turned out to be of surprisingly high quality! The very high resolution scans of the raw tapes are at Internet Archive.

I've also split them apart and uploaded them to YouTube, so here's a playlist of more than 24 hours of live performances at DNA Lounge spanning the years 1988 through 1992! Plus some other stuff.

We are also hosting a memorial for Spencer on the afternoon of Sat, Apr 4. If you knew him, please stop by!

As described previously, the Linux kernel security team does not identify or mark or announce any sort of security fixes that are made to the Linux kernel tree. So how, if the Linux kernel were to become a CVE Numbering Authority (CNA) and responsible for issuing CVEs, would the identification of security fixes happen in a way that can be done by a volunteer staff? This post goes into the process of how kernel fixes are currently automatically assigned to CVEs, and also the other “out of band” ways a CVE can be issued for the Linux kernel project.

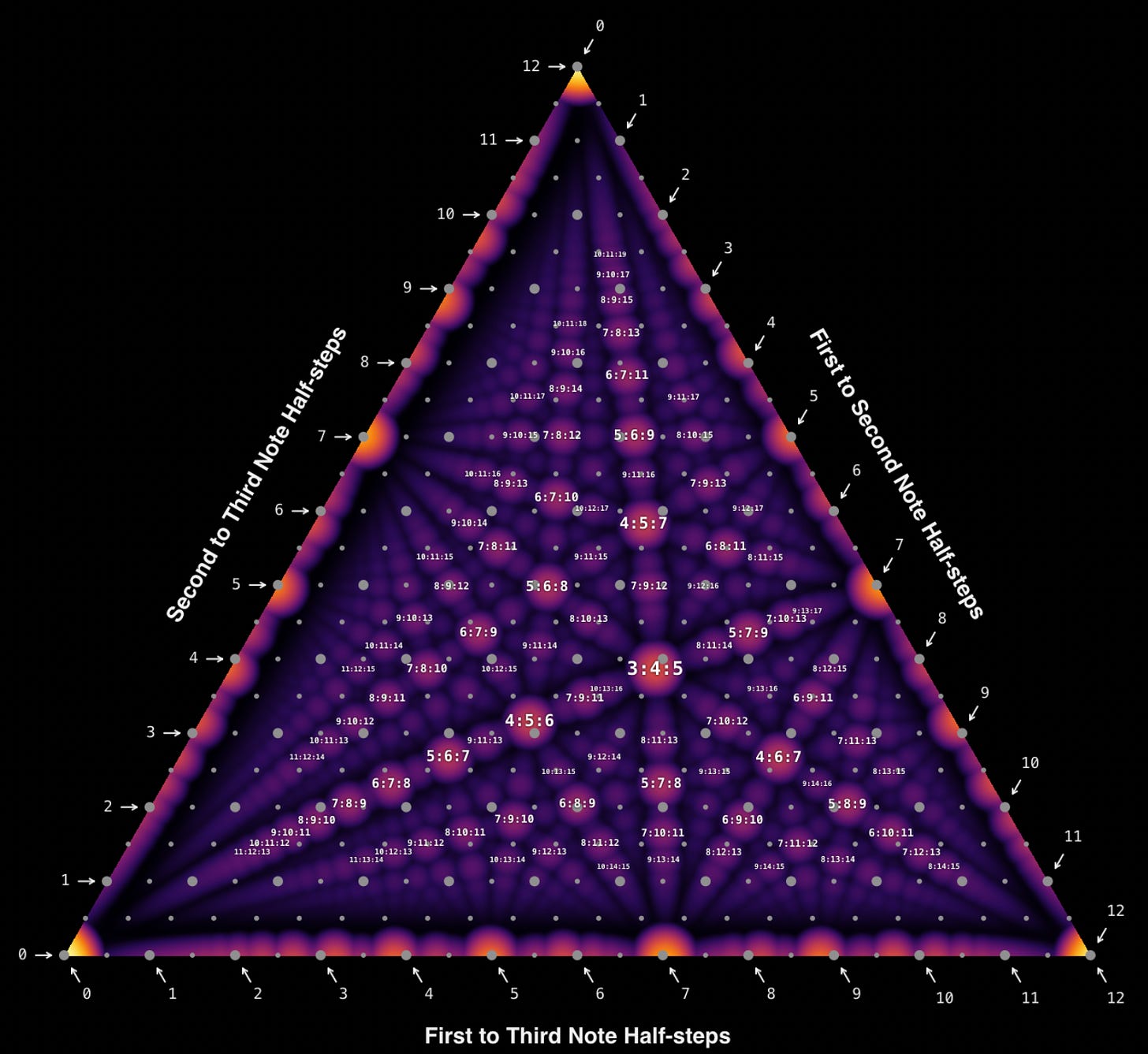

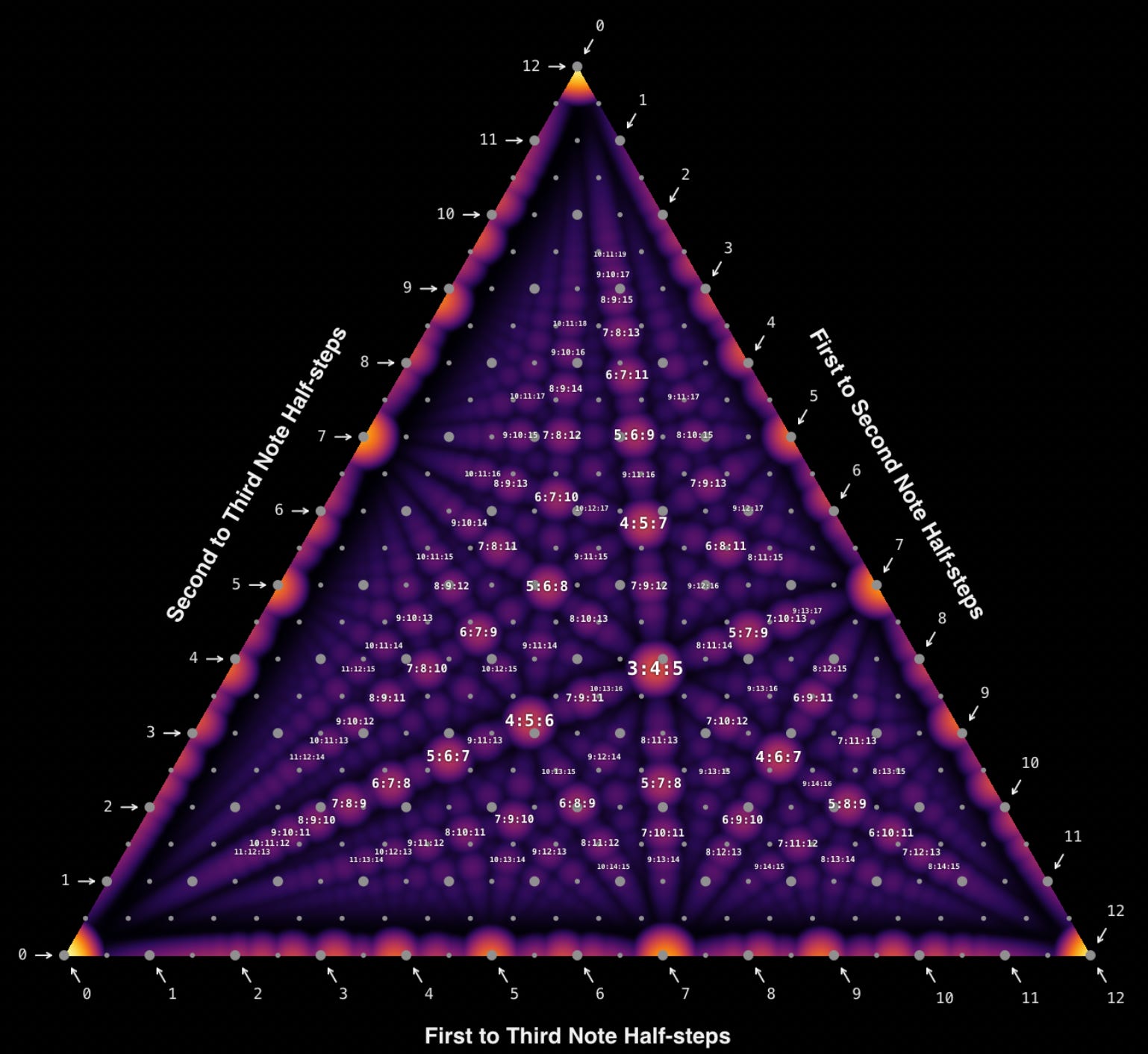

When playing melodies the effects of microtonality are a bit disappointing. Tunes are still recognizable when played ‘wrong’. The effects are much more dramatic when you play chords:

You can and should play with an interactive version of this here. It’s based off this and this with labels added by me. The larger gray dots are standard 12EDO (Equal Divisions of the Octave) positions and the smaller dots are 24EDO. There are a lot of benefits of going with 24EDO for microtonality. It builds on 12EDO as a foundation, in the places where it deviates it’s as microtonal as is possible, and it hits a lot of good chords.

Unrelated to that I’d like to report on an experiment of mine which failed. I had this idea that you could balance the volumes of dissonant notes to make dyads consonant in unusual places. It turns out this fails because the second derivative of dissonance curves is negative everywhere except unity. This can’t possibly be a coincidence. If you were to freehand something which looks like dissonance curves it wouldn’t have this property. Apparently the human ear uses positions where the second derivative of dissonance is positive to figure out what points form the components of a sound and looks for patterns in those to find complete sounds.

Here’s the story of a legendary poker hand:

Our hero decides to play with 72, which is the worst hand in Holdem and theory says he was supposed to have folded but he played it anyway.

Later he bluffed all-in with 7332 on the board and the villain was thinking about whether to call. At this point our hero offered a side bet: For a fee you can look at one of my hole cards of your choice. The villain paid the fee and happened to see the 2, at which point he incorrectly deduced that the hero must have 22 as his hole cards and folded.

What’s going on here is that the villain had a mental model which doesn’t include side bets. It may have been theoretically wrong to play 72, but in a world where side bets are allowed and the opponent’s mental model doesn’t include them it can be profitable. The reveal of information in this case was adversarial. The fee charged for it was misdirection to make the opponent think that it was a tradeoff for value rather than information which the hero wanted to give away.

What the villain should have done was think through this one level deeper. Why is my opponent offering this at all? Under what situations would they come up with it? Even without working through the details there’s a much simpler heuristic for cutting through everything: There’s a general poker tell that if you’re considering what to do and your opponent starts talking about the hand that suggests that they want you to fold. A good rule of thumb is that if you’re thinking and the opponent offers some cockamamie scheme you should just call. That certainly would have worked in this case. This seems like a rule which applies in general in life, not just in Poker.

Let’s say you wanted an offroad vehicle which rather than being a car-shaped cowboy hat was actually useful for camping. How would it be configured?

The way people really into camping approach the process is very strange to normal people and does a negative job of marketing it. You drive to the campground in a perfectly good piece of shelter and then pitch a tent. Normal people aren’t there to rough it, they’re there to enjoy nature, and sleeping in one’s car is a much more reasonable approach.

To that end a camper vehicle should have built-in insulation, motorized roll-up window covers, and fold-up rear seats. You drive to the campground, press the button for privacy on the windows, fold up the seats, and bam, you’re all set.

It should have a big electric battery with range extender optimized for charging overnight. The waste heat during the charging process can keep the vehicle warm while you sleep in it.

Roughly 8 inch elevation off the ground and a compliant suspension designed for comfort on poorly maintained roads rather than feeling sporty.

Compact hatchback form with boxy styling. Hatchbacks are already boxy to begin with and a flat front windshield works well with window covers so it’s both functional and matches the aesthetics.

Available modular fridge, induction plate, and water heater. With custom connectors to the car’s battery the electric cooking elements could ironically be vastly better than the ones in your kitchen.

Unfortunately having a built-in shower or toilet is impossible in a compact but the above features might be enough to make it qualify as a camper van which you’re allowed to live in. They’d at least make it practical to inconspicuously live in one’s car and shower at a gym.

Leela Odds is a superhuman chess AI designed to beat humans despite ludicrous odds. I’m a decent player and struggle to beat it with two extra rooks. It’s fun doing this for sheer entertainment value. Leela odds plays like the most obnoxious troll club player you’ve ever run into, more like a street hustler than something superhuman. Obviously getting beaten in this way is also humiliating, but it also seems to teach a lot about playing principled chess, in a way which raises questions about objectivity, free will, and teaching pedagogy.

Most computer chess evaluations suffer from being deeply irrelevant to human play. When decently strong humans review games with computer evaluation as reference they talk about ‘computer lines’, meaning insane tactics which no human would ever see and probably wouldn’t be a good idea for you to play in that position even after having been told the tactics work out for you in the end, much less apply to your more general chess understanding. There’s also the problem that the only truly objective evaluation of a chess position is one of three values: win, lose, or draw. One move is only truly better or worse than another when it crosses one of those thresholds. If a chess engine is strong enough it can tell that a bunch of different moves are all the same and plays one of them at random. Current engines already do that for what appear to be highly tactical positions which are objectively dead drawn. The only reason their play bears any resemblance to normal in those positions is they follow the tiebreak rule of playing whichever move looked best before they searched deeply enough to realize all moves are equivalent

So there’s the issue: When a computer gives an evaluation, it isn’t something truly objective or useful, it’s an evaluation of its chances of winning in the given position against an opponent of equal superhuman strength. But what you care about is something more nuanced: What is the best move for me, at my current playing strength, to play against my opponent, with their playing strength? That is a question which has a more objective answer. Both you and your opponent have a probability distribution of what moves you’ll play in each position, so across many playouts of the same position you have some chance of winning.

This is the reality which Leela Odds already acknowledges. Technically it’s only looking at ‘perfect’ play for its own side, but in heavy odds situations like it’s playing the objectively best moves are barely affected by the disadvantaged side’s strength anyway because the only way a weaker player can win is to get lucky by happening to play nearly perfect moves. And here we’re led to what I think is the best heuristic anyone has ever come up with for how to play good, principled, practically winning chess: You should play the move which Leela Odds thinks makes its chances against you the worst. The version of you playing right now has free will can look ahead and work out tactics but the version of you playing in the future cannot and is limited to working out tactics with only some probability of success. You can learn from advice from the bot about what are the most principled chess moves which give you the best practical chances assuming the rest of the game will be played out by your own not free will having self. Everybody has free will but nobody can prove it to anybody else, not even themselves in the past or the future. The realization that your own mental processes are simply a probability distribution does not give you license to sit around having a diet of nothing but chocolate cake and scrolling on your phone all day while you wait for your own brain to kick in and change your behavior.

Philosophical rant aside, this suggests a very actionable thing for making a better chess tutor: You should be told Leela Odds’s evaluation of all available moves so you can pick out the best one. The scale here is a bit weird. In an even position it will say things like your chances of winning in this position are one in ten quadrillion but if you play this particular move it improves to one in a quadrillion. But the relative values do mean a lot and greater ratios mean more so some reasonable interface could be put on it. I haven’t worked out what that interface might be. This approach may break down in a situation where you’re in an objectively lost position instead of an objectively won one and you should be playing tricky troll moves yourself. That seems to matter less than you might think, and could be counteracted by reverting to a weaker version of Leela Odds which can’t work out the entire rest of the game once it gets into such a position.

So far no one is building this. Everybody uses Stockfish for evaluation, which suggests a lot of lines you could have played if you were it, but of course you’re not, and is overly dismissive of alternative lines that would have been perfectly fine against your actual non-superhuman opponent. Somebody should build this. In the meantime if you want to improve your chess you’re stuck getting humiliated by Leela Odds even when you’re in what seem to be impossible to lose situations.

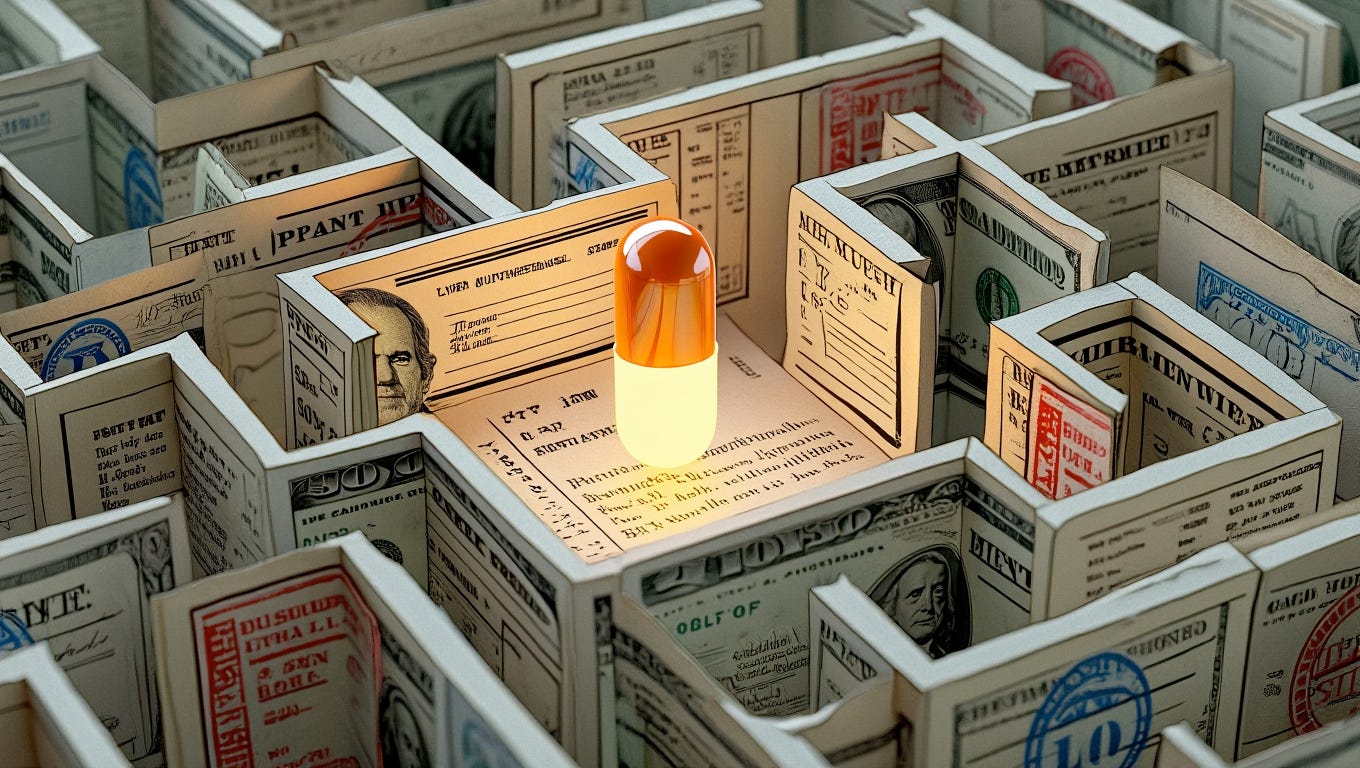

SR-17018 is a novel drug which is getting increasing underground usage for quitting opioids. It is technically an opioid itself but produces an amount of euphoria which is somewhere between barely noticeable and completely nonexistent. While taking it people don’t get withdrawal symptoms from Fentanyl but their Fentanyl tolerance fades at about the same rate as if they were going cold turkey without the SR-17018. People have been successfully using it to quit opioid addictions and even keeping a stash of it around in case they relapse, which is bizarre behavior for usually addicts. Usually if there are any opioids around they’ll take them and it will cause a relapse, so this stuff must really not be much fun or addictive. Opioids for opioid quitting has a bad reputation because of Methadone, but swapping Buprenorphine for Fentanyl is a big improvement and SR-17018 seems to be truly good for cessation. Unfortunately because it’s technically an opioid and there hasn’t been any movement on getting it approved for cessation purposes (it was originally studied as a painkiller which it’s unsurprisingly not very good at) most likely it will get shoved into schedule 1 at some point, sanity and reality be damned.

Varenilicline is a good smoking cessation drug but causes nausea in some people. The obvious fix would be to give patients Ondansetron with it. This has been suggested but doesn’t seem to have been tried, not even a case study. There seem to be two problems here: The drugs in question are generic and there’s no incentive to develop treatment improvements which are very cheap, and there’s a general view that any treatment of addiction is super scary and the patients should have to suffer, even for fairly safe drugs with no reason to think they’ll have a bad interaction.

Sodium Oxybate is about to get orphan drug status, for the second time, for the same drug, which is already making more than a billion dollars a year and was neither discovered nor characterized by the company which got the orphan drug status the first time. Pharma has the deeply broken structure that exclusivity periods are the only form of reward for research but a start to fixing it would be to make it that formulation changes are both much easier to get through and give much less exclusivity. A bare minimum start to that would be to clarify that orphan drug status was never meant to apply to formulation changes. It would also be good to make sectors which are already making massive profits not qualify as orphan any more and to reduce the exclusivity period for formulation patents in general, with time release formulas and salt changes handled as specific special cases.